How Apple Achieved a 0.005% Income Tax Rate

In 2014, Apple Inc. paid an effective corporate income tax rate of just 0.005% in Ireland. That’s not a typo—it’s five ten-thousandths of a percent. To put this into perspective, if you earn 1 million annually and pay 250,000 in personal income tax (assuming no other deductions), Apple would need to earn 5 billion to pay the same amount of tax.

This tax rate was confirmed by the European Union after a two-year investigation. Neither the Irish government nor Apple disputed the accuracy of these figures, so the information is reliable. Following the investigation, in August 2016, the EU ordered Apple to pay €13 billion in back taxes to the Irish government for the period between 2004 and 2014. If Ireland were to impose penalties, the amount could rise to €20 billion, making it the largest tax bill in history. Apple decided to appeal this decision to the European courts.

The Apple tax case raises several intriguing mysteries:

- Mystery 1: How did Apple legally achieve a 0.005% tax rate in Ireland?

- Mystery 2: While Apple’s decision to appeal is understandable, why did the Irish government also appeal? Don’t forget, Ireland is a small country with a population of just 5 million, and its 2017 fiscal revenue was only €67.6 billion. If Ireland collected Apple’s taxes and penalties, it could boost national revenue by one-third. Moreover, this money was essentially forced upon Ireland by the EU—why would they refuse such a windfall?

- Mystery 3: In July 2020, the European General Court ruled in favor of Apple. How could Apple justify a 0.005% tax rate and still win the case?

- Mystery 4: After the controversy, Apple didn’t stop its tax avoidance strategies. Instead, in 2015, it replaced its previous tax scheme with a new one. What’s so special about this new method that Apple continues to push the boundaries?

- Mystery 5: The most puzzling aspect is that Apple’s ultimate goal is to avoid U.S. taxes. While the EU was furious at Apple’s tax avoidance, the U.S. government didn’t step in to collect taxes. Instead, it accused the EU of acting as a "supranational tax authority." Why does the U.S. tolerate such large-scale tax avoidance by its corporations?

In this article, we’ll explore these questions in five parts:

- How did Apple achieve a 0.005% tax rate?

- Why did Ireland refuse to take the billions?

- Why did Apple win its case?

- Why does Apple continue to avoid taxes?

- Why does the U.S. tolerate corporate tax avoidance?

Let’s dive in!

I. How Did Apple Achieve a 0.005% Tax Rate?

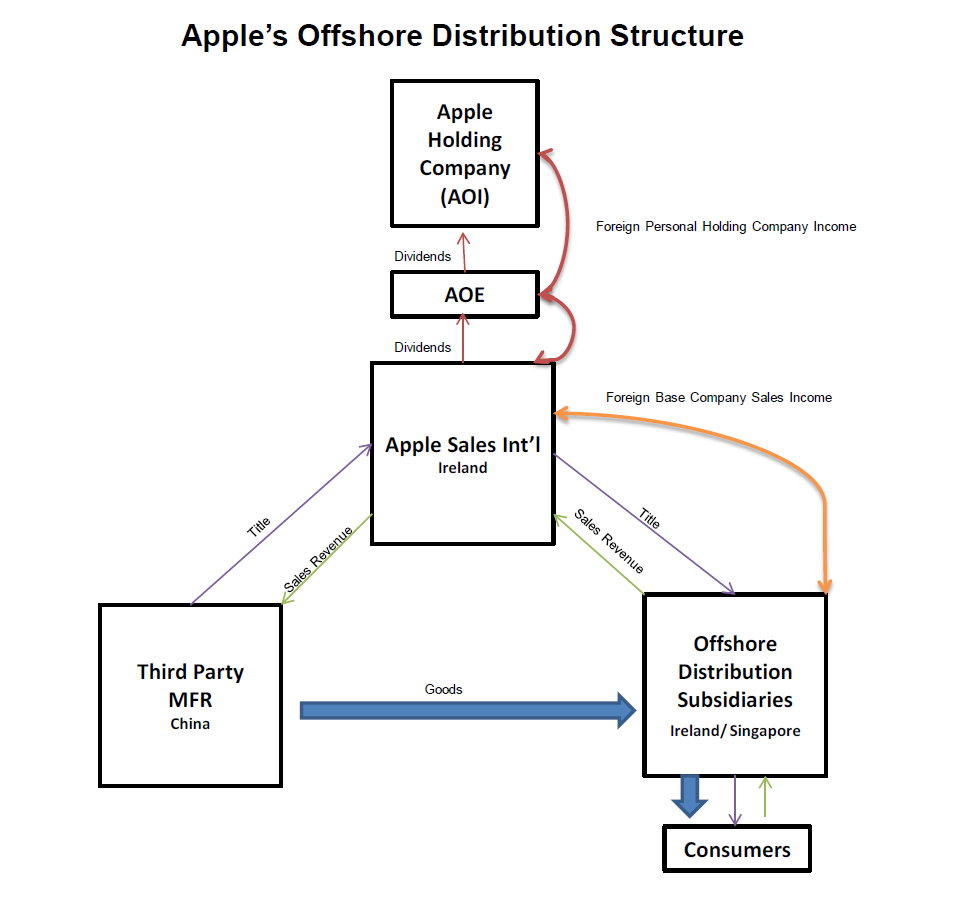

Below is a diagram of Apple’s 2014 Irish holding structure and its financial and operational flows. Using this complex structure, Apple legally achieved an effective tax rate of 0.005% in Ireland. Let’s break it down step by step:

Step 1: Shifting Profits to Ireland

Apple established a company in Ireland called Apple Sales International (“ASI”) (center of the diagram). ASI purchased fully assembled Apple products from Chinese factories (“Third Party MFR China”, bottom left of the diagram) at cost and then sold them to offshore distribution subsidiaries (“Offshore Distribution Subsidiaries”) at near-retail prices. This allowed ASI to retain most of the profits in Ireland.

Example:

If an iPhone costs 3,000 to produce and sells for 7,000, ASI would purchase it from the Chinese factory for 3,000 and sell it to offshore subsidiaries for 6,500. Out of the 4,000 profit per iPhone, ASI would retain 3,500.

Step 2: Using a Branch Structure to Classify Most Profits as Non-Irish

ASI employed an unprecedented branch structure, splitting itself into a "stateless head office" and an "Irish branch office". Most of ASI’s profits were attributed to the stateless head office, while only a small portion was allocated to the Irish branch. The head office was exempt from Irish taxes, while the branch office was subject to Ireland’s corporate tax rate, resulting in an effective tax rate of 0.005%.

Example:

Out of ASI’s 3,500 profit, 3,498.6 was attributed to the tax-exempt head office, and only 1.4 was allocated to the taxable branch office. With Ireland’s corporate tax rate of 12.5%, the branch office paid 0.175 in taxes (1.4 × 12.5%), achieving an effective tax rate of 0.005% (0.175 ÷ 3,500).

You might think the Irish tax authorities would reject such an absurd arrangement. Shockingly, not only did they accept it, but they also issued tax rulings in 1991 and 2007 formally approving this structure.

Step 3: Creating a Tax Black Hole to Avoid U.S. Taxes

Apple Operations International (“AOI”) (top of the diagram) was an Irish-registered company managed in Bermuda. AOI was wholly owned by Apple in the U.S. and indirectly controlled ASI. Under Irish law at the time, a company’s tax residency was determined by its place of management, not its place of incorporation. As a result, the Irish tax authorities agreed that AOI was managed in Bermuda and therefore exempt from Irish taxes.

Under U.S. tax law, however, residency was based on the place of incorporation, meaning AOI was considered an Irish company. As long as AOI didn’t distribute dividends to Apple in the U.S., all income flowing from ASI to AOI was exempt from U.S. taxes, effectively creating a tax black hole.

Step 4: Using Cost-Sharing Agreements to Repatriate Funds Tax-Free

The major flaw in this tax strategy was that overseas profits couldn’t be directly repatriated to the U.S. So what did Apple do when its U.S. headquarters needed funds? No problem—Apple’s U.S. headquarters signed a Cost Sharing Agreement with ASI. Under this agreement, the U.S. headquarters conducted R&D while ASI bore a portion of the R&D costs in exchange for acquiring the rights to Apple’s intellectual property (“IP”) outside the U.S.

This arrangement allowed Apple’s U.S. headquarters to receive tax-free funding for R&D expenses, while ASI acquired foreign IP and continued its Irish tax avoidance scheme without facing U.S. capital gains taxes or transfer pricing risks.

Additionally, AOI served as a cash pool, providing low-interest loans to the U.S. headquarters through internal lending with external guarantees (e.g., the U.S. headquarters issued bonds guaranteed by AOI). Since AOI was cash-rich, lenders saw minimal risk, resulting in low interest rates. AOI’s interest income was tax-free, while the U.S. headquarters could deduct its interest expenses.

II. Why Did Ireland Refuse to Take the Billions?

The EU ordered Apple to pay €20 billion in taxes and penalties for the period between 2004 and 2014. This amount represented one-third of Ireland’s 2017 fiscal revenue. Logically, Ireland should have happily accepted the windfall. So why did it appeal the EU’s decision?

The answer lies in Ireland’s national strategy: facilitating tax avoidance is a cornerstone of its economy. Although Ireland is an EU member, it is one of the world’s largest tax havens.

You might be surprised—aren’t tax havens typically Caribbean islands like the British Virgin Islands (“BVI”), Cayman Islands, or Bermuda? How could an EU country be a tax haven, let alone the largest? After all, the EU is a leading force behind global anti-tax-avoidance efforts (e.g., BEPS). How can it fight tax avoidance while allowing one of its members to facilitate it?

Technically, Ireland doesn’t meet the traditional definition of a tax haven, as its corporate tax rate is 12.5%, not 0%. However, Ireland is the epicenter of tax avoidance for U.S. multinationals, as evidenced by the following data:

- In 2015, Apple’s tax restructuring caused Ireland’s GDP to grow by 34.4%. Today, Apple alone contributes 20% of Ireland’s GDP.

- U.S. companies account for 80% of corporate taxes paid in Ireland.

- U.S. companies employ 25% of Ireland’s workforce.

- Half of Ireland’s top 50 companies are U.S. corporations.

- According to tax expert Gabriel Zucman, the effective tax rate for U.S. multinationals in Ireland was just 4% in 2018, far below the statutory rate of 12.5%.

- In 2017, Ireland’s central bank adopted a Modified GNI metric to exclude tax-avoidance-related GDP distortions and reflect its true economic output.

Ireland’s goal in facilitating tax avoidance is to drive economic growth, tax revenue, and employment. Unlike China’s manufacturing-driven economic strategy, Ireland’s approach is simpler and faster: attract U.S. multinationals by exploiting loopholes in U.S. tax law.

When the EU targeted Apple’s tax avoidance, it was also targeting Ireland’s tax avoidance industry—a cornerstone of its economy. If Ireland had accepted Apple’s €20 billion "golden egg," it risked losing the entire tax avoidance "golden goose." Without its tax haven status, multinationals would have no reason to stay in Ireland. Thus, Ireland had no choice but to resist the EU’s decision, fight the global anti-tax-avoidance movement, and continuously refine its tax laws to remain a haven for tax planning.

Corporate tax avoidance may be infuriating, but it thrives because of supportive environments and policies. Some countries deliberately cede taxing rights to attract foreign investment, enabling widespread tax avoidance.

III. Why Did Apple Win Its Case?

After the EU was formed, member states retained their taxing rights, leading to a patchwork of tax laws and rates across the union. Countries like Ireland and Luxembourg exploited this disparity by creating tax policies that attracted multinational corporations, allowing them to legally concentrate their European profits in these jurisdictions. While the EU has long sought to reform this system, it faces significant challenges—taxing rights are a core symbol of national sovereignty, and countries like Ireland depend heavily on their tax-avoidance industries for economic growth.

Although the EU is aware of these avoidance schemes, it is often powerless to act. Under the Treaties of the European Union (one of the EU's constitutional foundations), member states have the right to tax—or not tax—as they see fit. This raises an important question: On what legal grounds did the EU demand that Apple pay back taxes to Ireland?

The EU’s legal basis was State Aid.

What is State Aid?

State Aid refers to government measures that provide financial advantages to certain companies, giving them an unfair competitive edge. Article 107 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union prohibits such practices to ensure open markets and fair competition, and the European Commission has the authority to monitor compliance.

The EU argued that Ireland allowed Apple to use ASI’s head-office/branch structure to avoid taxes and protected this arrangement with tax rulings. Since Ireland did not offer similar tax benefits to other companies, Apple gained an unfair advantage over competitors, violating State Aid rules. Therefore, the legal dispute centered on whether Ireland had created a tax tool specifically tailored for Apple, rather than on the tax avoidance itself.

In July 2020, the European General Court ruled in favor of Ireland and Apple. Importantly, this ruling did not validate Apple’s tax avoidance practices; rather, the court found that the branch structure and Ireland’s tax rulings did not distort market competition enough to violate State Aid rules.

From a technical perspective, Apple’s branch structure was simply a simplified version of the well-known Double Irish tax scheme. By adding one more Irish subsidiary, Apple could have achieved the same tax-avoidance results. Since the Double Irish structure was widely available to other companies—not just Apple—it was unlikely to create an unfair advantage. This may explain why the EU lost its case. We’ll have to wait and see how the EU’s appeal develops.

IV. Why Does Apple Continue to Avoid Taxes? Apple’s New Tax Scheme

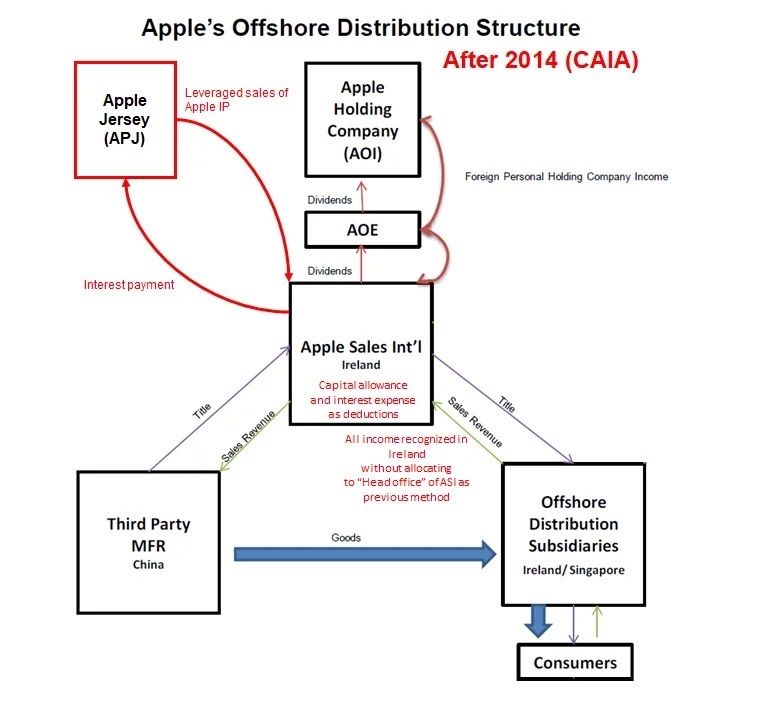

Most companies facing massive tax bills would stop their tax-planning activities, right? Not Apple. While it terminated its head-office/branch structure in 2015, it didn’t stop avoiding taxes—it simply switched to a new tool: Capital Allowances for Intangible Assets (“CAIA”). This change was the main reason Ireland’s GDP surged in 2015.

CAIA is similar to Article 67 of China’s Corporate Income Tax Law, which allows for the pre-tax amortization of intangible assets. While public information does not disclose the specifics of Apple’s use of CAIA, we can make educated guesses based on available data. The red-highlighted sections in the diagram below summarize the process, which we’ll break down step by step:

Step 1: Transferring Intellectual Property (IP) to ASI at Market Value

Apple Jersey (“APJ”, top left of the diagram) held the IP rights for Apple products sold outside the U.S. In 2015, APJ transferred the IP for the iPhone 6 to ASI at a market value of $100 billion. Assuming development costs were $30 billion, the $70 billion profit from the sale was tax-free in Jersey (a known tax haven).

Step 2: ASI Acquires the IP Using Interest-Bearing Debt

ASI didn’t pay the $100 billion upfront; instead, it borrowed the amount from APJ. Assuming an interest rate of 5%, ASI paid $5 billion annually in interest, which was tax-deductible in Ireland. Meanwhile, APJ’s $5 billion in interest income was tax-free in Jersey.

Step 3: Leveraging CAIA for Tax Savings

After the transaction, ASI recorded the $100 billion IP asset on its financial statements. Assuming a CAIA amortization rate of 30%, ASI could deduct $30 billion annually (up to the $100 billion total). Combined with the $5 billion in interest payments to APJ, ASI could deduct $35 billion annually. As long as ASI’s profits from the iPhone 6 didn’t exceed $35 billion, it wouldn’t owe any taxes in Ireland.

In the future, ASI could repeat this process with other IP assets, maximizing their valuations to increase tax deductions. Using CAIA and interest payments, Apple could continue its tax-avoidance strategies indefinitely.

Step 4: U.S. Anti-Tax-Avoidance Measures Fail

In 2017, the U.S. enacted the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (“TCJA”), which introduced a new 10.5%–13.125% tax on Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (“GILTI”)—profits derived from low-taxed foreign intangible assets. However, since the new U.S. tax law allowed CAIA deductions, Apple avoided GILTI taxes and continued to pay no U.S. taxes on its foreign profits.

In summary, CAIA is even more advantageous than Apple’s previous head-office/branch structure:

- The old scheme required Apple to allocate a small portion of profits to the Irish branch and pay taxes, while the new scheme eliminates taxes entirely (even the 0.005%).

- The old scheme was subject to U.S. GILTI taxes, while the new scheme avoids them.

- Transferring IP to Ireland allows Apple to leverage Ireland’s extensive tax treaty network for reduced withholding taxes on royalties, which Jersey lacks.

V. Why Does the U.S. Tolerate Corporate Tax Avoidance?

Apple’s primary tax-avoidance target is the U.S. If the U.S. taxed Apple’s Irish profits, the entire avoidance scheme would collapse. Yet when the EU fined Apple €13 billion, the U.S. didn’t criticize Apple—it accused the EU of acting as a "supranational tax authority." Why does the U.S. tolerate such large-scale tax avoidance by its corporations?

Unlike emphasis on lawful taxation, the U.S. has a very different cultural and historical attitude toward taxes. Here are a few examples:

1. Founding Values

One of the key events leading to America’s founding was the Boston Tea Party in 1773, where colonists protested against Britain’s tax policies on tea imports. One of their grievances was that Britain’s tax policies gave the East India Company an unfair competitive advantage in America.

American values emphasize individual responsibility and the American Dream, which focuses on upward mobility through personal effort. These values often clash with the concept of collective responsibility and public finance through taxation.

2. Income Taxes Were Unconstitutional for a Long Time

In 1872, the U.S. abolished income taxes after the Civil War. In 1894, Congress attempted to reintroduce income taxes, but the Supreme Court struck them down as unconstitutional in 1895. It wasn’t until 1913 that the 16th Amendment resolved the constitutional issue, allowing income taxes to be levied.

3. Reagan’s Tax Philosophy

When Ronald Reagan became president in 1980, he believed that the government’s role was to protect private property and that economic growth depended on maximizing corporate profits. He argued that lower taxes would stimulate economic growth. In 1986, Reagan successfully overhauled the tax system, reducing the top income tax rate to 28%, the lowest among developed nations at the time. Reagan’s comments on taxes reflect his philosophy:

"This country was built on the belief in the individual, not groups or classes, and the belief in the resources and wealth of every soul."

"Our Founding Fathers… never envisioned the progressive income tax as we know it today."

"Calling the tax code un-American is not an exaggeration."

"We must not forget that our country was founded in resistance to oppressive taxation. Our Founding Fathers fought not just for political power but also for economic freedom. Without economic freedom, political freedom is just a shadow."

Reagan’s policies profoundly influenced modern U.S. tax policy. Even Donald Trump’s tax policies followed Reagan’s philosophy of tax reduction. While Joe Biden, a Democrat, has proposed higher taxes on the wealthy, the current political climate in the U.S. makes it difficult to implement significant tax increases. Instead, the focus is likely to remain on strengthening anti-tax-avoidance measures.

For companies like Apple, tax planning is purely a financial calculation: comparing the benefits of tax savings against the risks and costs of compliance. As long as the benefits outweigh the risks, nothing will stop multinationals from pursuing tax avoidance.

Note: This article is part of a paid subscription series. If you enjoyed this content, please consider subscribing for access to more high-quality articles on international taxation.